Brice continued to flatten the implied physical space of his paintings, often complicating it by offering multiple, simultaneous views around axially rotated forms. One of Picasso’s favored ploys, in his hands—in the double portraits of the 1930s, for example—the device assumed psychological overtones, suggesting the ego and the alter-ego. In contrast, Brice’s multiple views are about physicality, more specifically, about conducting the eye, its intelligence, and, by extension, the body though space. The body is the measure of all of Brice’s canvases, which range in scale from hand-held to full body to mural size. He situates the image in direct relationship to his own body, and part of the frankness that accompanies his pictures is the steady sense that in nearly every instance there is a degree of self-portraiture. Certainly in the starkest and most frontal image, Brice’s own body language looms large. His need to engage the viewer in his art and the verbal-respondent in his life, is closely allied.

During the remaining years of the 1970s, Brice created a group of large, light, iconic paintings marked by a startling formality that brings the larger than life personages into the viewer’s pace. The female form especially takes on mythic proportions. Radiant with sunlight, the pictures seem optical transcriptions of the hazy luminescence of Los Angeles, and Brice’s drawn line gains proportionately to his emptying out of any modeled and darkened space. In Untitled, 1978 (plate 68), a strong, vertical painting, he abbreviates forty years of observation in only a few lines: the sinuous contours of the body, a flanking geometric scheme on either side, and poignantly rendered horizontals across top and bottom. Between the two parallels—the limits of mind above and of body below—Brice breathes life into a spare and diaphanous universe.

A tonal painter by nature, Brice slowly reintroduced contrasting atmospheric color in these ethereal works. For example, an untitled 1978 picture

(plate 57) employs a bright red rectangle and an irregularly shaped, cloudlike blue form as emotional frames for internal, discursive drawing: the red holds various linear suggestions of the masculine, while the blue apparently symbolizes a container or substitute head for the female thought waves. With this work Brice arrives at the fullest exploitation of both color and line in his work. In isolating and superimposing the expressive means within a larger image, he is able to construct many paintings-within-a-painting, and to replicate the ceaseless sense stimuli and intellectual ordering that constitute consciousness.

Brice constructs another kind of “environment” for his abstracted figure in this period, as well. Here space is fixed exclusively by color and paint application in wetter and more nuanced color grounds. Held in this aqueous space, the figural motifs are situated at some distance from the painting’s surface and so from the viewer.

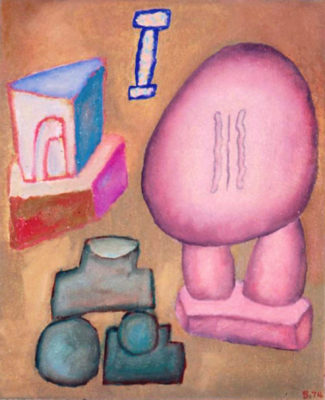

figure 9. Untitled, 1974, oil on emery cloth, 11 x 9 in. Collection of Norman and Frances Lear

These paintings, a large 1978 untitled canvas (plate 65) typical of them, reveal meaning slowly and often only in part. Informed by the sfumato of Brice’s drawings, they are frequently darker paintings, night-like, perhaps somnambulant. Their crowded organization suggests the rapidity of images that comes with sleep.

This suite of paintings came to a conclusion around 1978; the same year companion exhibitions surveying his work from the early 1970s were held at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art and the Nicholas Wilder Gallery. His move in 1975 to a large industrial shed, generously dotted with skylights, had borne great fruit. The two exhibitions proved Brice’s vision could comfortably take on grand proportions while retaining its airy other-worldliness. Despite Brice’s repeated adjustments of surface, some of them having been painted and erased for more than five years, he managed to impart a rare grace to both line and color.

Repeating his pattern of exposure followed by self-imposed seclusion, Brice developed his work in private in the years after 1978. In 1984 he again moved his studio, this time out of Los Angeles proper into a nondescript light industrial section of the San Fernando Valley. This most recent and current studio, too, is high, boxy, and amply skylit. In the work he completed after moving there in 1984, Brice reprised the earlier post-and-lintel arrangements, this time enlarging the composition to full canvas size. In their delicate and localized washes of color, and in their formal resemblance to windows or doorways, these paintings

(plate 62) (plate 66) may portend the reintroduction of an architecturally inspired anatomy of unusual lightness and serenity in work yet to come.

Passages of more opaque overlaid color appear in these recent paintings, as well.

Untitled, 1984

(plate 70), features a sinuous rivulet of turquoise and a torqued connector of differently colored rectangular planes. A kindred form twists through an ambiguously identified anatomy in another untitled painting

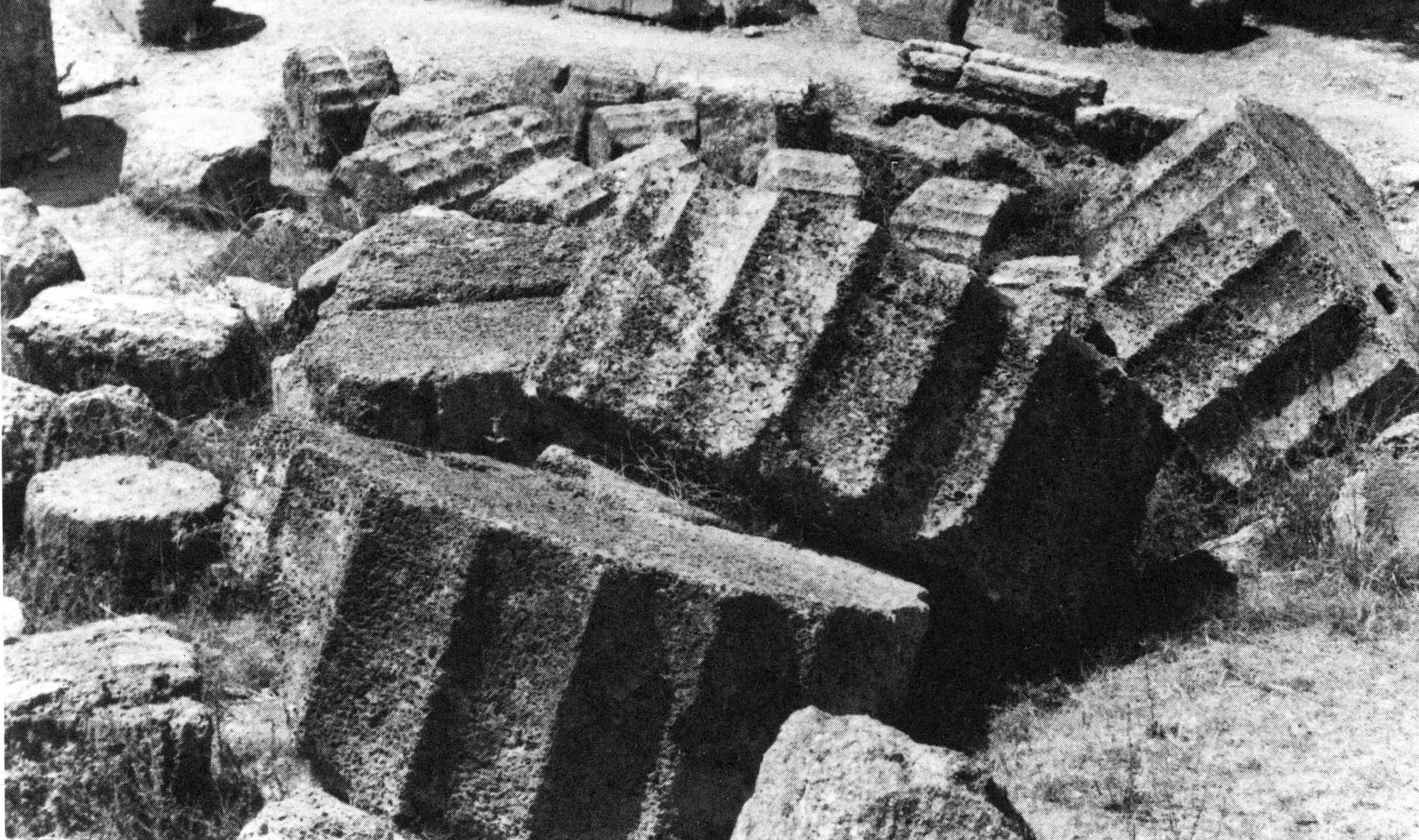

(plate 72) done the following year. The left half of this composition approximates the stonestrewn terrain Brice remembered from Greece, a recollection further manifested by the oversize carved head that lies here on its side, its mottled grey face home to yet another set of drawn forms.

The largest of the paintings from that moment, an untitled work 108 by 108 inches

(plate 71), grandly unites Brice’s favored motifs. As is often the case, the picture divides into halves. A grey and blue stack of forms balances precariously on the left, seeming to gesture to the linear skeleton at right. An arch of faint, whitish blocks underlies the latter, setting up an intense oscillation between line and colored mass. But in contrast to most of Brice’s earlier paintings and to their clearly demarcated formal and symbolic oppositions, a third figure, fused and androgynous, hovers at its middle. With this small third form Brice introduces the independent image of mediated sexual fusion between the two monumental figures. The new-found equilibrium of associations enriches the painting’s meanings. In this most recent phase of Brice’s work there are no true opposites: thus the figure with the giant resting head in an untitled painting of 1985

(plate 72) seems, if anything, polysexual. Old dichotomies seem only two versions of the same thing. The fullness of his vision admits the range of temporary accuracies we cling to as truth. The central paradox of Brice’s career has been the realization that there can be clarity in ambiguity.

In conversation, Brice once referred to his two private categories for painters: recorders and conjurers. His long and steady evolution as an artist embodies the transformation from one to the other. For Brice, painting has been an activity of constant articulation. Working at first from his response to the world around him, Brice has gradually converted that external reality to one inside himself. From his responses, intellectual and sensual, to the reality around him, Brice has gradually interchanged external and internal, communal and personal, universal and particular. Inventing symbols for his essential elements, he fashions a mythic narrative of man, woman, and world, and the light, color, and form that both separate and connect them.

Longer quotes by the artist are from Jascha Kessler, “William Brice: An Interview,” Art International 23 (September 1979). All other quotes by the artist are from conversations with the author in August 1984 and December 1985.

NB Corrections:

1. Brice moved to Los Angeles with his family in 1938 (not 1937)

2. Brice bought his Picasso in 1934 at 13 (not 14)

3. His first one-person exhibition at a commercial venue was in 1949 (not 1948).

4. Brice began his teaching career at UCLA in 1954 (not 1953).

5. Brice’s studio at his home was designed by Neutra’s contractor, Red Marsh, on Neutra’s recommendation.