Between Stability and Chaos: Part Three (of 6)—A Mentor for Life

Art is a collision of new truths and awakened sensibilities; it is a serious understanding of the untried and unexpected.

Henry Botkin,

10 Years of Painting, Exhibition Catalogue,

Lowe Art Gallery, Syracuse University,

October 10 – November 9, 1971

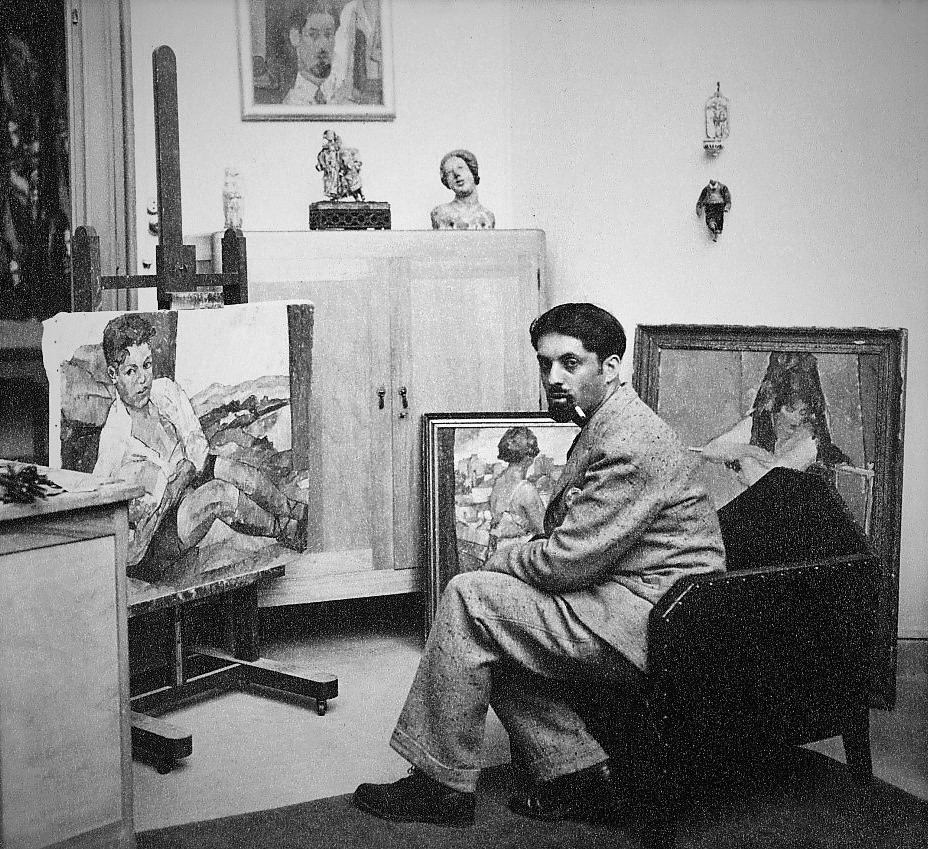

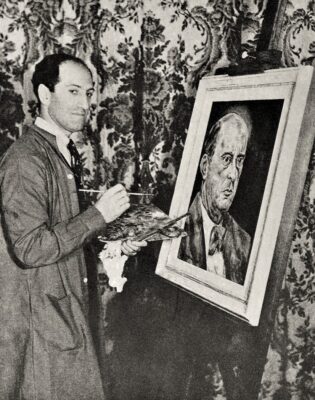

The Mentor

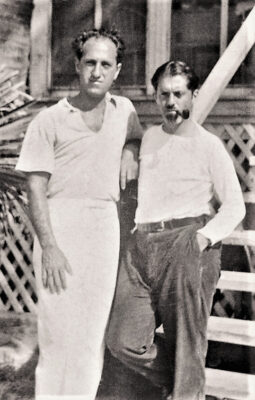

It was natural that Fanny would recommend her 13-year-old son study art under Henry Botkin. She knew he was giving art lessons to her good friend and his cousin, George Gershwin. She was aware, too, that Botkin was his cousin’s curator, helping Gershwin amass a world-class art collection, and that Botkin was a well-regarded New York artist.

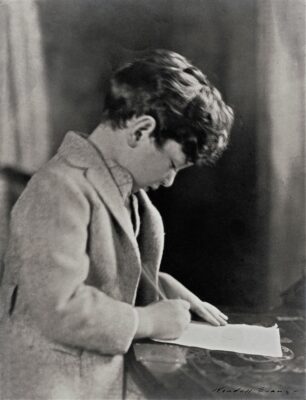

The Student

Brice spent his earliest years mostly bereft. His father abandoned him and his family when he was six years old. Throughout Brice’s formative years, his mother’s theatrical career made her largely unavailable to him. Thus, his care was left to disengaged governesses who mistreated him. As a preadolescent, Brice spent months convalescing in a sanitarium recovering from rickets and pectus excavatum (soft, concave sternum bones). What young Brice did have, in abundance, was plenty of uninterrupted time to ‘live in his head’, to observe his environment, to imagine, and to invent images. He became a habitual ‘drawer’.

Brice and Botkin

One can imagine the 13-year-old’s feelings the day he met Botkin, his new personal art teacher, a professional artist—who came to Brice’s mother’s home, not to see her, but just for him.

Here was a patient, kind, intelligent, articulate, and deeply thoughtful man who was filled with curiosity. He was still young at 38-years-old, nearly 20 years younger than Brice’s absent father. And contrary to his father, Botkin was invested in something bigger than himself—in his love and reverence for art and its history of art makers. And he, too, was devoted to ‘looking’ and making.

For over a year, Botkin visited Brice two to three times a week. He worked with Brice on the essentials of interpreting space, light, tone, line, shape, form, color, and compositional relationships. He also took the young man out to Manhattan’s remarkable museums and its many galleries, where they wandered through exhibitions looking and discussing what was before them. Botkin acquainted the 13-year-old with art from around the world: African, Assyrian, Egyptian, Indian, Islamic, Japanese, Chinese, and European art: Greek, Roman, Medieval, Gothic, Renaissance, Rococo, Impressionism, and so on to modern and avant-garde art.

Botkin was a generous man in young Brice’s life, who enjoyed and encouraged the teen, rather than ignoring or reprimanding him.

Brice came to admire Botkin and, through him, became fascinated with modernism. In particular, his evolving appreciation for Botkin’s seven years spent living and working in Paris grew into respect for what it meant to be an artist in Paris at that time—the then capital of the avant-garde in art and culture and the undisputed center of global art.

Moreover, Botkin’s neighbors in the 1920s were Braque and Derain. Botkin knew many of the artists who were part of “the School of Paris” in the twenties as he helped to subsidize himself by bringing forty to fifty paintings by these artists with him whenever he returned to New York. He would then sell works by artists including Picasso, Braque, and Gaugin to American collectors, including his cousin, George Gershwin.

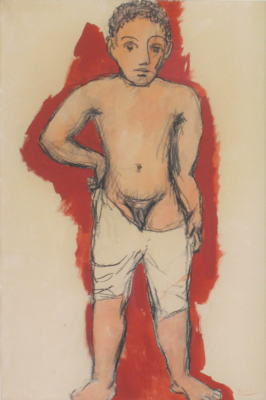

How do we know Brice was captivated by Botkin and by what he was learning about modern art? Because Brice chose to buy his first artwork out of his savings—from that $25 that his mother had deposited into his own bank account every month since his birth. The work he chose was Boy in Drawers, a 1906 Picasso gouache that Brice purchased for $350 in 1934, or in today’s money, $8,000. How unusual it was, and would be today, for any teen to spend $8,000 on a work of art.

The other thing we know is that Brice had a particularly sophisticated eye, especially for a thirteen-year-old.

Indeed, Vienna’s Albertina Museum recently requested Boy in Drawers for its exhibition, Modigliani – Picasso: The Primitivist Revolution, September 17, 2021, to January 9, 2022, writing:

The following work from your collection is of particular importance for our exhibition: The young boy represents a particularly beautiful example from a series of male nudes painted at Gósol, Catalonia, in the spring and summer of 1906.

Many of these nudes are framed by a reddish background maybe inspired by Matisse and the Fauves. The absent-minded gaze, oversized eyes of the boy bear witness to Picasso’s engagement with Iberian or Romanic Spanish sculpture at that time, while the hieratic posture is closely connected to the archaic sculpture the artist had admired at the Musee du Louvre a few months earlier.

Brice treasured the work for the rest of his life.

Green Shoots

In Botkin and art, Brice had begun to discover a kind of stability within himself and in his life, which became apparent. As his mother observed of her quiet son, “When he started talking, we couldn’t shut him up. Oh, boy!”

However, Fanny’s career had also begun to change: Hollywood had called. In 1928, Warner Brothers offered Fanny her first starring role in My Man, which was to be based on Fanny’s hit Broadway/Ziegfeld show number of the same title. It would be only the second ‘talkie’ ever made and the first to star an actress. Fanny took it. More starring roles with extended trips to Hollywood ensued. Then, in 1937, when Brice was 16, Fanny was offered her own weekly, nationally broadcast radio show, Baby Snooks, also based on a Ziegfeld character Fanny had invented. It was to be broadcast from Los Angeles to America.

For the first time in her life, the radio show offered Fanny a day job, and so the chance to settle down, to enjoy meals and weekends with her children—and to finally be a family.

Brice and his sister listened in astonishment as Fanny told them that she had accepted an offer to star in her own radio show the following year and so they were moving to Los Angeles, to the other side of America, and to a town that was still a near backwater. She intended to build a magnificent new mansion with a swimming pool, located on two acres in Bel Air where legendary movie stars lived—and that Fanny just bought.

His mother’s plan for her career and her family abruptly ended Brice’s relationship with Botkin, with art, and with himself. Chaos again.

To be Continued – See our Next Blog: Between Stability and Chaos: Part Four (of 6)—“California Here I Come”