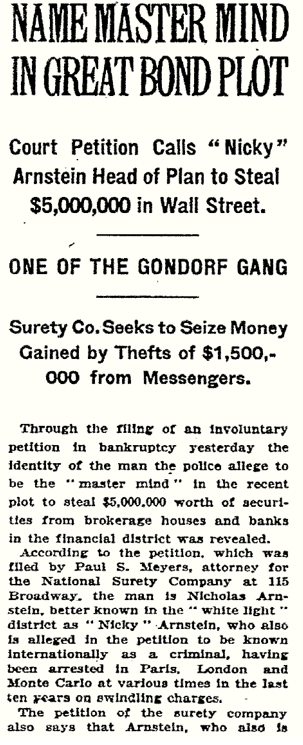

Between Stability and Chaos: Part Two (of 6)—Julius ‘Nicky” Arnstein, Convicted Felon and Father

Everything Nicky ever did was like a gentleman…He was a very well-educated man, had a great manner, and was very cultured. At parties, he would be surrounded by people ten minutes after he entered a room. He was a good speaker. Of course, half of the things he would be telling them were lies.

He was crazy about W.C. Fields, and vice versa…That’s the first time that Bill Fields ever heard anybody say, “Never give a sucker an even break” – “Never wisen up a sucker.” He heard that from Nicky. And, of course, Nick would be telling him all lies – exaggerated stories – and W.C. Fields just loved them all.

[Nick] never worried about anything. In 1920 he would say, “In 1921 I’m going to have a million dollars.” In 1921 he would say, “In 1922 I’m going to have a million dollars.”…When he would start in on a new one, he would start with such vigor. For two or three weeks, he would be at his office at eight o’clock, and if it didn’t start going right away, he would start losing interest and would show up at about twelve or one o’clock, and then not at all. He would then go back to working with some of the wise guys because he was such a good front for them – he looked so good.

Fanny Brice,

Interview Recording, ca. 1950

Society’s rules did not apply to Nick, or so he believed. As a result, he was drawn to personalities and activities that twice put him in prison on felony convictions—and nearly did a third time.

Nick and Criminality

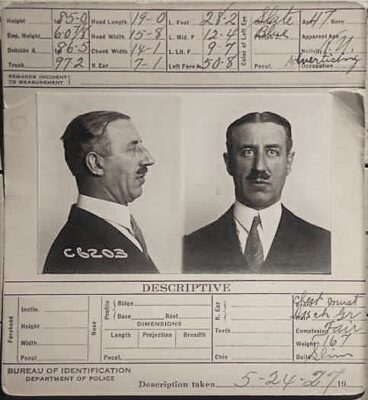

Nick’s vocation was not “professional gambler”, who followed the elegant and romantic racetrack crowd around the country, as he had intimated to Fanny in 1912 when they first met. That was a con job.

He was a sophisticated confidence man, who sailed on elegant ocean liners to bilk wealthy, grey-haired widows and naive debutantes out of their money. In fact, Nick had been arrested for swindling in London, Paris, and Monte Carlo between 1909 and 1912, but was never imprisoned. Fanny, normally clear-eyed and streetwise, was too crazy about this elegant man to see the con. They moved in together—without Nick letting her know that he was still married to his estranged wife. Another con.

Then in 1915 while living with Fanny, Arnstein was charged with using an illegal wiretap as part of a scheme to swindle stocks and was sentenced to fourteen months in Sing Sing. Fanny visited him in prison—and so did Nick’s wife although Nick kept Fanny unaware. Yet, another con.

By 1918, though, Nick’s wife finally agreed to divorce Nick, and in October of that year, he and Fanny were legally wed.

Then the big trouble began. In 1919 Arnstein organized a Wall Street robbery that focused on the ‘rigged’ hold up of messengers carrying $5,000,000 in Liberty Bonds, which in today’s money would be approximately $86,000,000. Once the gunmen were found, they began to talk; and news of Nick’s involvement began to leak. He ‘went on the lam’ for six months and became the FBI’s most wanted man in North America. Fanny’s home was searched. The Feds began tailing her everywhere.

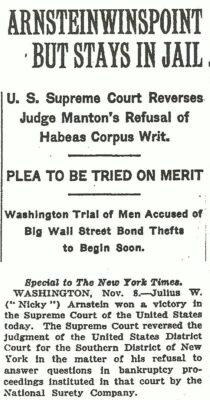

Eventually, the Manhattan District Attorney offered a deal: If Nick turned himself in, Nick would receive a reduced sentence if convicted. Nick did. Three years of trials and appeals ensued. His case reached all the way up to the Supreme Court (and became an addition to the Constitution’s 5th Amendment).

In the end, Nick was sentenced to three years in Leavenworth Prison, which began in 1924.

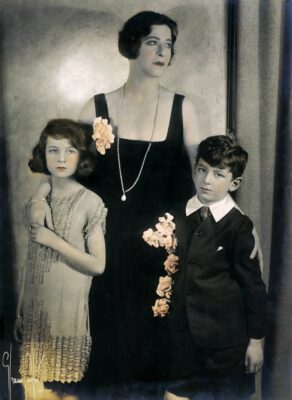

Brice was born simultaneously with the start of his father’s court battles (1921), which played out in newspaper headlines across America. Baby Brice had little access to his father during this period. He was just three when Nick began his three-year prison sentence.

By the time of his father’s release in 1927, Brice was six. But his newly returned father was not particularly interested in either of his children and six-year-old Brice had only months to get to know his father at all.

Julius Nicky Arnstien as a Father

You just never knew how [Nick] felt about the children…there was something very peculiar about him. He led a life of kidding himself all the time…Every time I was pregnant, he hated to see it. I’d get out of bed – and he’d go for my robe – to get me covered up…I’d have liked him to say, “Let me feel it.” No, he wasn’t that way. He was embarrassed and uncomfortable with any part of the truth.

Fanny Brice

Interview Recording, ca. 1950

Break up of Brice’s Parent’s Marriage

The end began on a summer day when Fanny looked forward to hosting friends for lunch at hers and Nick’s second home on Long Island. In preparation that morning, she asked Nick to rent a boat so they could take their guests fishing as after-lunch entertainment. “I’ll be right back, Honey,” Nick told her. But he did not come “right back”, nor did he come back for lunch, nor for the after-lunch entertaining, nor for dinner with Fanny—it wasn’t until midnight that Nick finally showed up.

“What happened to you?” challenged Fanny—knowing the boathouse was only a block away. “The car broke down,” was all Nick offered. Fanny was furious. She knew he philandered but was incensed at his lazy reply: “Am I not worth a good lie? You won’t make up an excuse – that’s the only excuse you’ll give me – ‘The car broke down?’”. An argument ensued. A few days later Nick retreated to Chicago.

Fanny hired detectives to follow him and search for proof to support her suspicions. Indeed, Nick was having an affair. This and Nick’s arrest in Chicago for owning and operating an illegal gambling house led Fanny to realize that she had finally had enough—that she did not like the man she loved. It was over.

Then, on August 18, 1927, when Brice was six, a New York times headline shouted:

NAME ARNSTEIN IN RAID; Chicago Police Say Big Gambling Resort Is Run by New Yorker

A month later Fanny divorced Nick:

Despite Nick’s subsequent marriage in 1932 to a Pasadena heiress and his son’s eventual relocation to Los Angeles, just a forty-minute drive door to door between father and son, Nick only bothered to see Brice three more times before his death in 1965.

It’s Not Over – More Chaos, Again

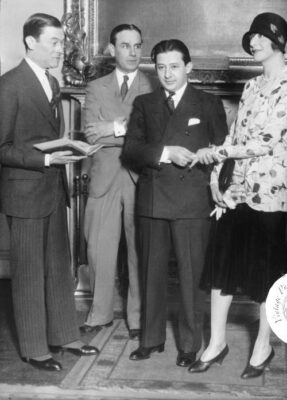

Two years after she divorced Nick, Fanny married her third husband, Billy Rose, in 1929.

Brice was eight when this ‘new man’ moved into his home.

Rose was as different to Brice’s father as day is to night. And his background was opposite to Brice’s, and even to his mother’s. Similar to Fanny, Rose was the child of Jewish immigrants, but that is where any similarities end. While Fanny grew up in a Manhattan lower middle-class

life, Rose’s Bronx family was poor. He was also 7 inches shorter and 8 years younger than Brice’s mother.

However, Rose was ferociously intelligent and, in the parlance of the period, was a go-getter. He relentlessly studied shorthand during his high school years and became a world champion with the ability to take over 200 words per minute. He also taught himself to write forward or backward with either hand.

At the young age of seventeen, he became stenographer to the great and extremely wealthy financier, Bernard Baruch, after President Wilson appointed Baruch to head of War Industries Board at the advent of America’s entry into WWI.

Following the war, Rose turned himself into a lyricist after learning that popular ditties earned lyricists extremely high incomes with impressively low overhead expenses: just paper and pencil. Between 1927 and 1933 alone, Rose penned lyrics for several hits that are still well known: Me and My Shadow (1927), More Than You Know (1929), Without

a Song (1929), I Found a Million Dollar Baby (in a Five and Ten Cent Store,) 1931, and It’s Only a Paper Moon (1933).

But Rose aspired to more and so he next turned himself into a Broadway producer. In 1931, he produced, directed, and wrote the book for Billy Rose’s Crazy Quilt, starring Fanny Brice.

Brice would grow to respect Rose, but they never developed a close relationship.

And What Did his Mother’s Friends Model for Brice?

Some friends managed to lead relatively happy, ‘normal’, productive lives like the Eddie Cantors, who loved each other and their five daughters. But others led self-destructive lives until it killed them. W.C. Fields and John Barrymore died of alcoholism. The brilliant Oscar Levant became a ‘dope’ addict who went in and out of mental institutions near the end of his life, which came at a young 66. And then there was Kiki Preston, a beautiful wealthy American, who had many lovers, including Rudolph Valentino and Prince George, Duke of Kent. She was one of Brice’s mother’s Beverly Hills acquaintances and her daughter became a girlfriend of Brice’s just before he met his future wife. Miss Preston had for a time been part of the notorious Happy Valley set in Kenya, a group of hedonistic aristocrats and adventurers. There, Kiki was known as “the girl with the silver syringe” for obvious reasons. She finally leaped to her death from a window of her fifth-floor apartment in Manhattan’s tony Stanhope Hotel.

Did the “quiet” boy, as his mother described, want to escape from such turmoil? Did he feel lost in the miasma surrounding him? Did he gravitate towards the safe and predictable, and so seek some ‘secure’ profession possibly in law, business, or banking such as Fanny’s friends Bernard Baruch or Frank Murphy?

Did he contemplate a life in the arts and aspire to producing, directing, or acting? Or in music like his mother and her ‘creative friends’?

Or did he seek something entirely different? Or just to be a Ne’er-do-well?

What about Fanny? Was she concerned for her son—did she notice him?

I saw him drawing – doing automobiles and airplanes – and I asked him if he liked it. He said he did. And I asked him if he would like a teacher. So, I got Henry Botkin – the Gershwins’ cousin…And the one thing that Botkin did teach him – the first thing, was to learn to work – that it’s a full-time job. You just don’t start and then stop. The thing I was worried about in regard to Bill – I was afraid he’d be like me. I wouldn’t study for anything – I would make it come itself. I had to get everything from here (heart). But I knew that if he painted, it had to happen up here (head), too!

Fanny Brice

Interview Recording, ca. 1950

* * *

To be Continued – See our Next Blog: Between Stability and Chaos: Part Three (of 5)—A Mentor for Life