DRAWINGS OF WILLIAM BRICE

Drawing is a continuous activity for me. Increasingly I feel that I want to act upon any idea or image that passes through my mind. I want to grasp it, to mark it. I also find that one drawing begets another, and the idea develops. I rarely use a drawing as a direct study for a painting. The drawings have a life of their own. They establish a vocabulary that I develop in painting. So, the drawings and the paintings coexist. They are interactive. It’s significant that some of the most moving works are achieved in drawing.

Interview with William Brice

by Wendy Diamond and Constance Lewallen

View, Vol IV, No. 6 Spring 1988, Crown Point Press

William Brice moved easily between drawing and painting, producing more drawings over his career than works in other media. For some artists, drawings are low in the hierarchy of media with painting at the apex. Not so for William Brice. His paintings and drawings “coexist”.

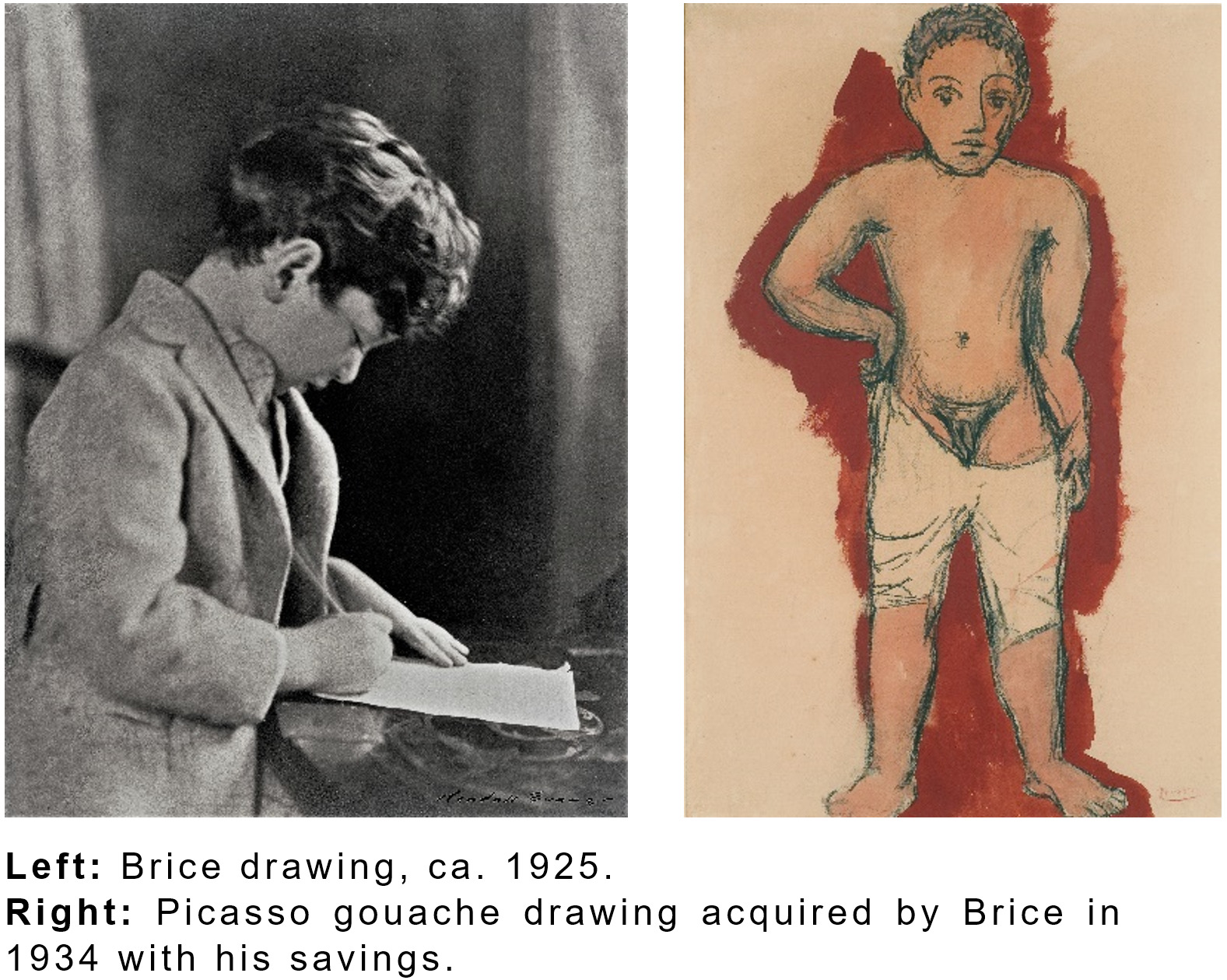

Brice first put pencil to paper when he was just a child of three or four. A few years later, he filled the sidewalk of the entire block in front of their Upper West Side block with chalk drawings. At 13 he purchased his first work of art, a gouache drawing by Picasso. By age 16, Brice knew that becoming an artist was his life’s path. His life in New York afforded him opportunities to visit many of the finest art museums and galleries in America with his tutor, artist Henry Botkin.

Many artists and art historians feel that drawings provide the most direct record of the artist’s hand. For the artist, they are easier, less complicated to create. As Brice said, drawing has an “absence of paraphernalia”. There are no mechanical steps to take, as in producing lithographs, etchings, or woodcuts. Nor must one prepare canvases by stretching or treating the surface with gesso.

Drawing can be both means and ends. As a process, it can be revelatory in its directness and intimacy. It can capture the fleeting feeling and record the idea forming. A notebook of drawings is, in this sense, a diary of responses. The surprising complexity of nature, our nature, replenishes drawing. Easy generalizations are dispelled as the hand moves with marvelous particularity in response to the feelings that direct it. The rich variety of processes and materials of drawing permits infinite possibilities. As in the other media, the ends are realization, meaning, and expression. In brief notation or elaborate development, drawing can offer all this without loss of its essential immediacy.

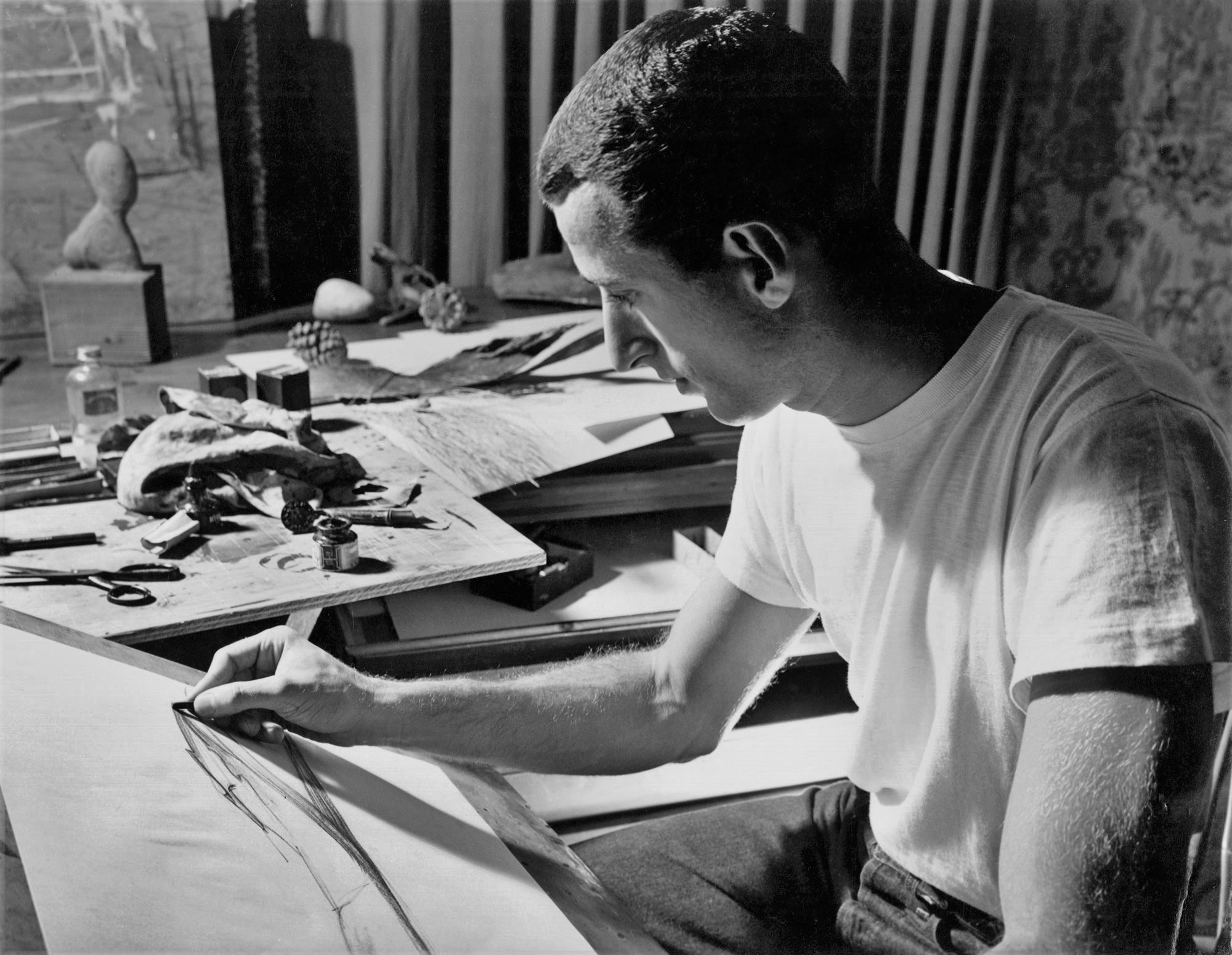

William Brice, circa 1965

These “infinite possibilities” are most definitely found in the wealth of drawings Brice executed over his lifetime.

Elegance and Mastery

Brice, erudite and intelligent, brought his profound awareness, self-awareness, and his ability to synthesize his multiple responses to the manifold meanings he found in his subjects to each new drawing.

Simultaneously, he marshaled diverse strategies of expression for each. This included his inclinations toward compound interplays and juxtapositions of elements and his extensive and sophisticated visual vocabulary.

His oeuvre evidences a particularly elegant and wide array of formal qualities of line, tone, form, shape, and texture—all of which would sometimes be deployed in a single drawing, making these drawings seem almost musical—jazz-like with disparate visual riffs that magically combine to make an overall, unified statement.

Yet, artists like Ed Moses have remarked over Brice’s ability to create drawings of seemingly continuous, sharp line, drawn without any evidence of hesitation, even in complex compositions. These drawings appear remarkably effortless as Brice’s line appears to flow directly from mind, to eye, to hand, to paper at once.

Other drawings might be ‘worked’ like sculpture: additive and subtractive processes combined in the same work.

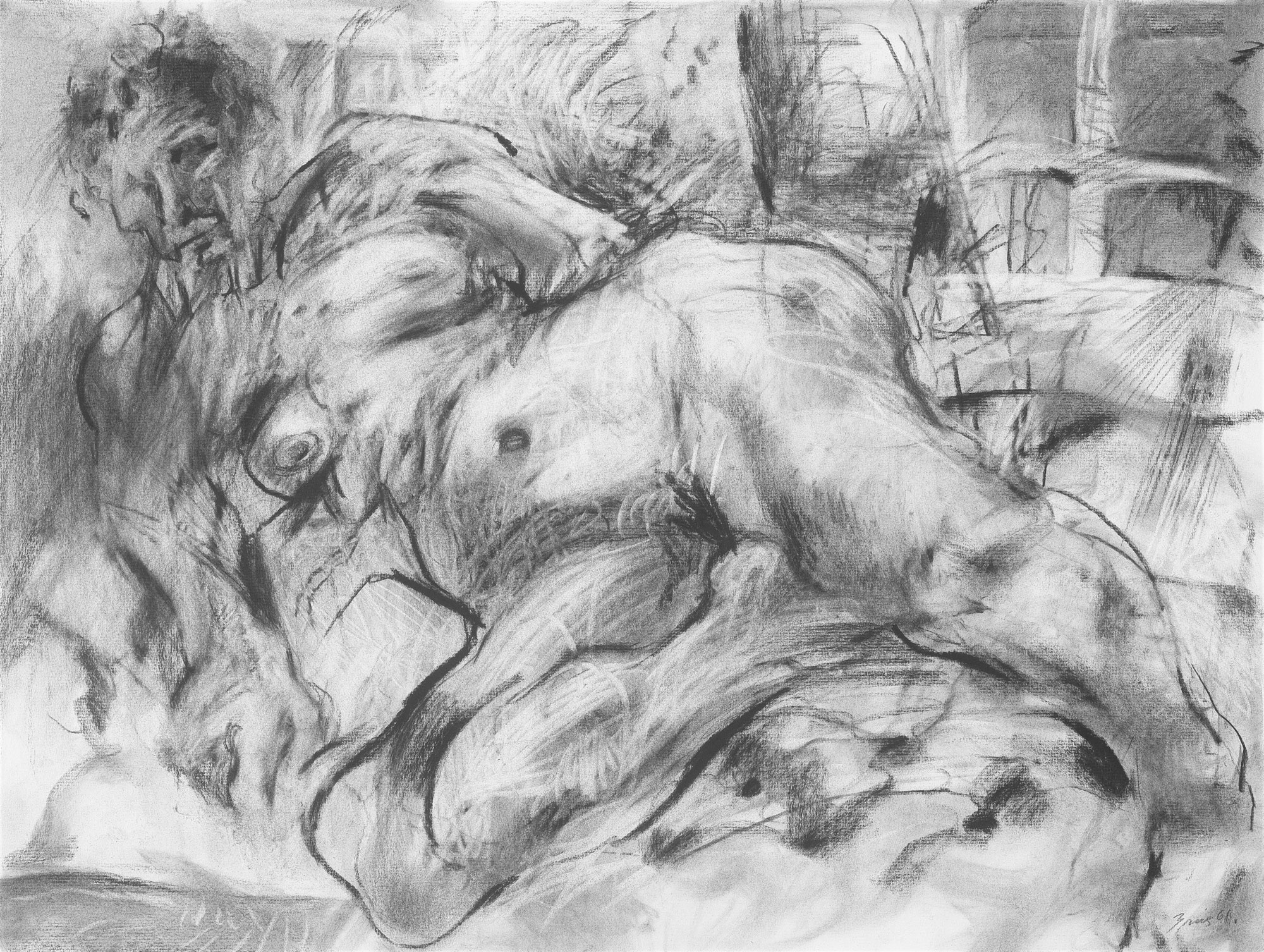

Ed Moses made insightful observations about the drawing below in Some Other Exotic Place, But Seen From LA, YouTube, 2011:

[This 1961 drawing] is either simultaneous or previous to Lucian Freud’s formations…about figuration, about a body. And this body has two parts…which I particularly like. (Ed’s hand circles the hip and leg area— ) This formation is almost abstract, set out in front of this formation (gestures towards the torso), and then this head that has nothing to do with the character here.

There is this stacking here of lines, dusting of formations, roundness, setting volumes, taking a kneaded eraser and taking out. So, there’s a kind of history that stacks back and forth, and then that history coalesces into ‘now’.

He may make a mark. He defines an edge with a very loose line and then a very hard line. And then there is the dusting of the charcoal. Maybe he charcoaled the whole thing and then drew into that and cleaned it out. But this thing here is so intriguing (Ed’s hand circles around the area of the knee, legs and hip, again). It’s like this bold thing sticking out in front. And then this (pointing to the belly mound), and then these breasts. And then these two formations here (pointing to the black, circular, smudge marks on the hip and the bellybutton). I love this drawing; I love this drawing.

And then suddenly these little lines here (pointing to razor-sharp charcoal lines at the lower window ledge). Are they radiations from the light coming out of the window or are they just markings? And the interesting thing is that the markings can become descriptive, illustrative, or they can just be markings in terms of the fact of the markings. So, this in my mind is a masterful drawing. It has no history. It’s forever.

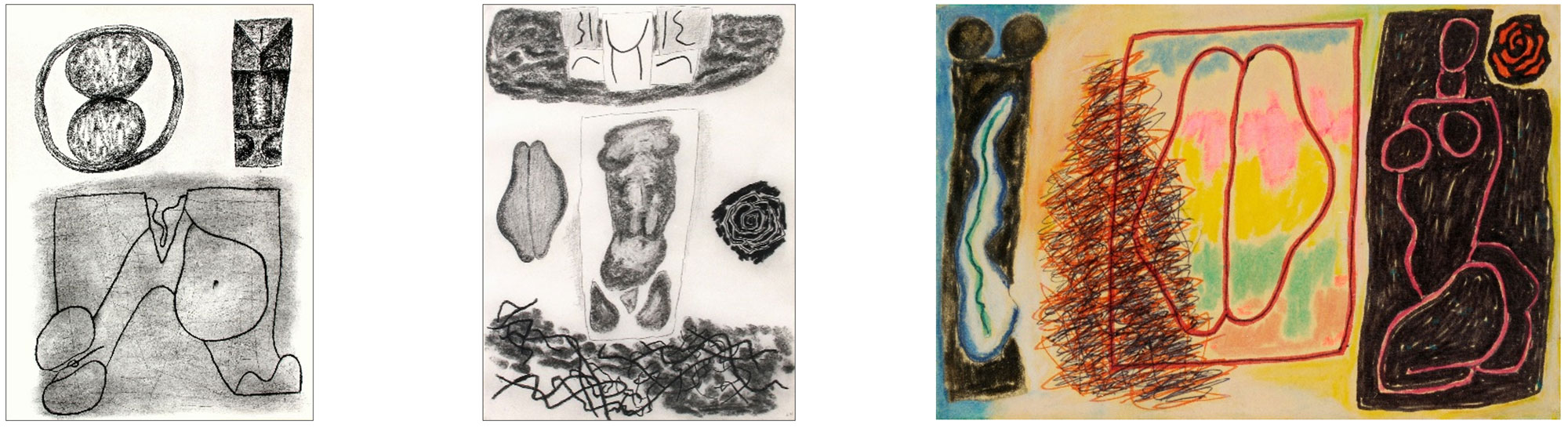

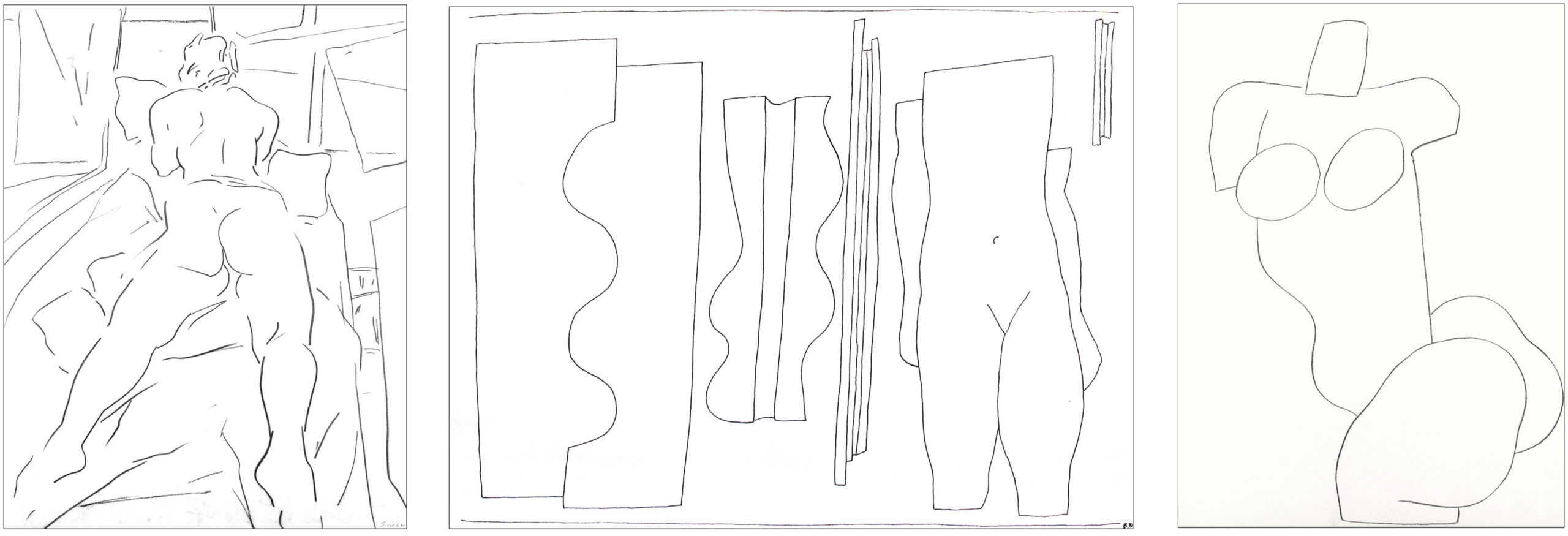

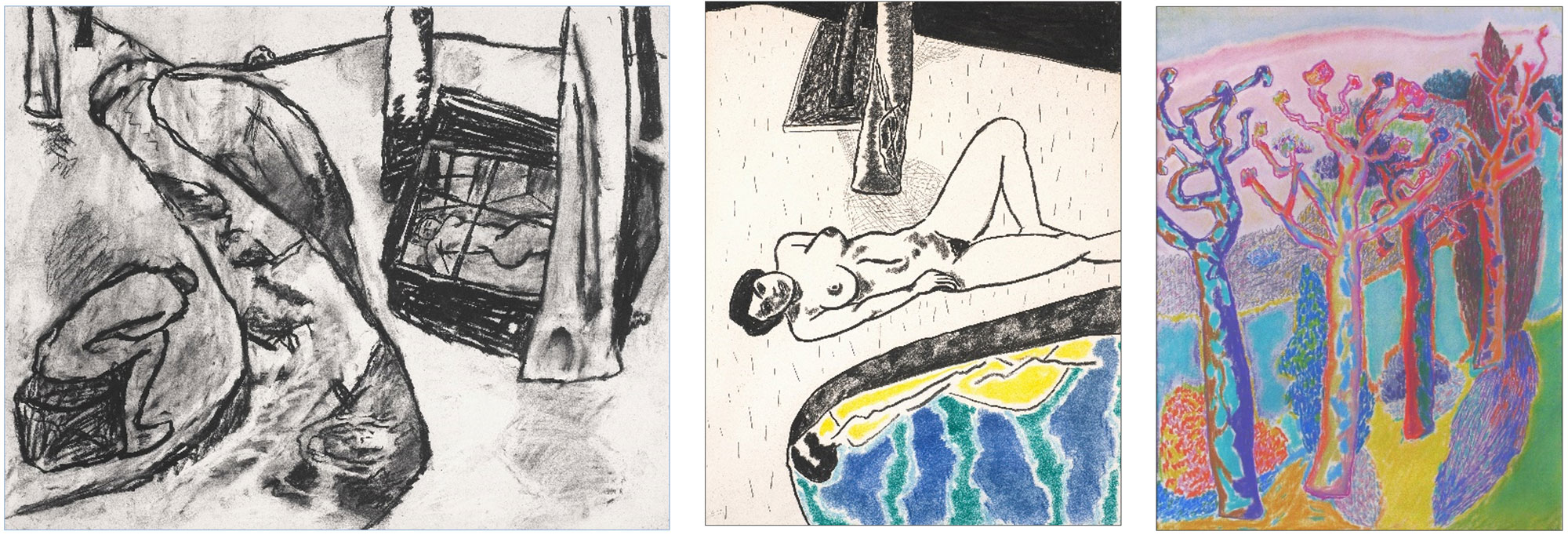

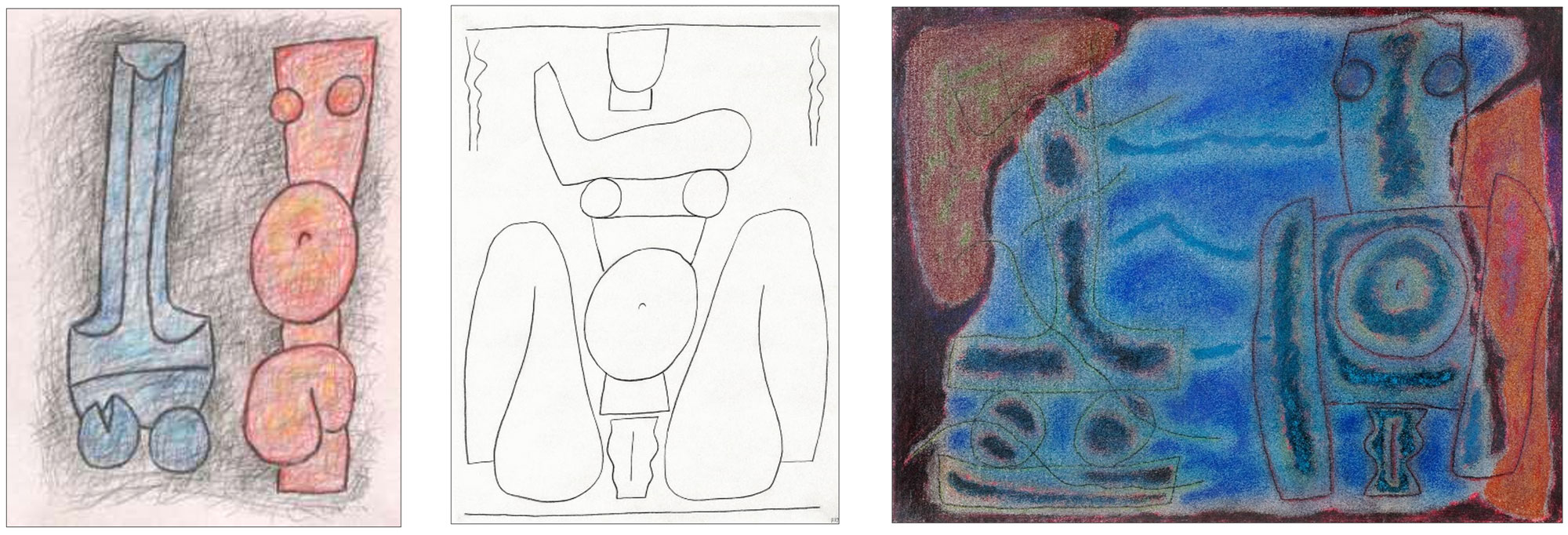

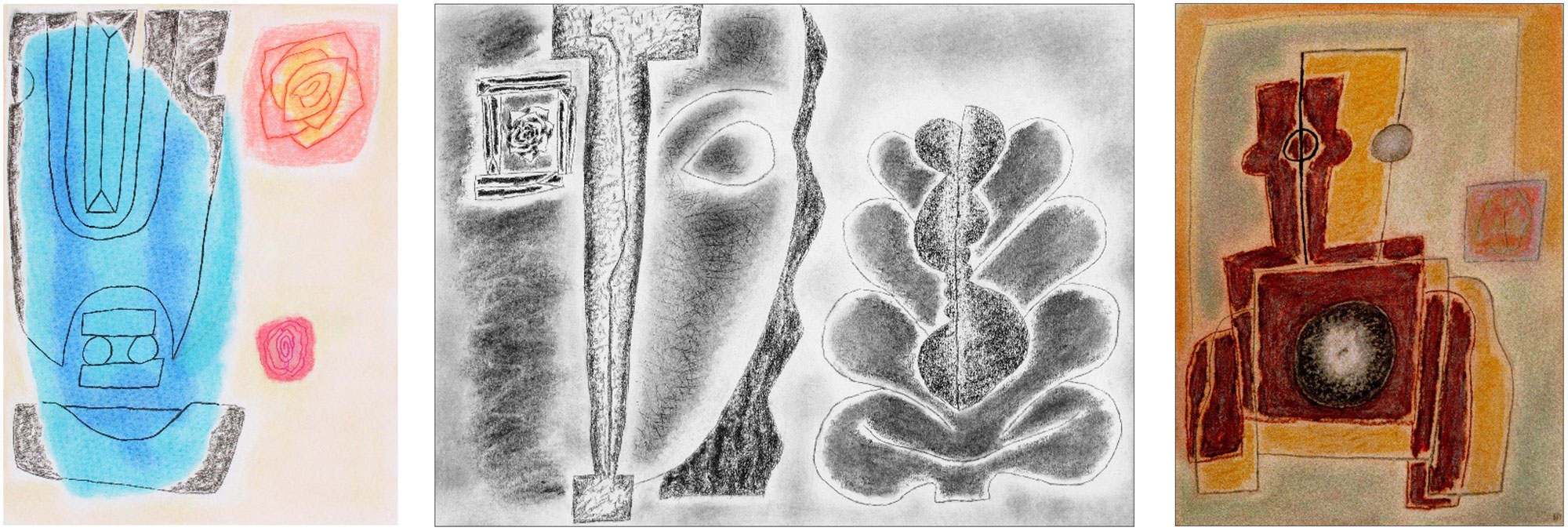

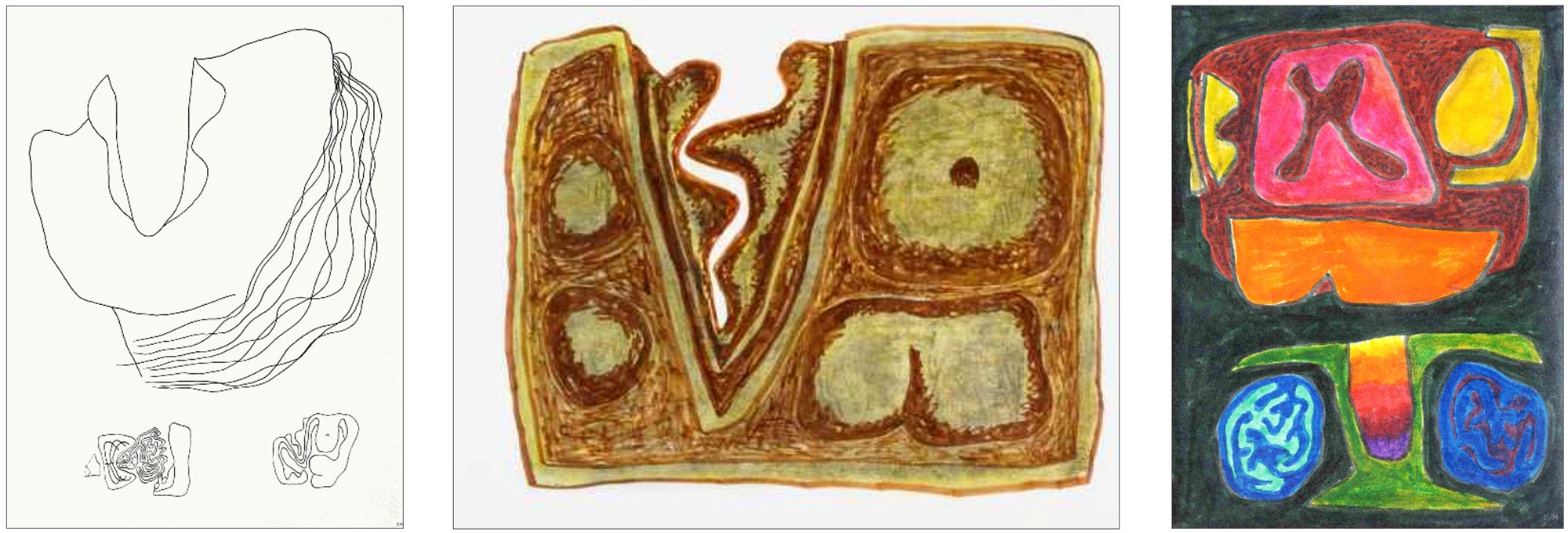

Brice Drawing by the Decade

Decade by decade, Brice’s drawings reveal a deeply personal and emotional journey in addition to an artistic one. Early depictions of nude, female figures have a classical, romantic tinge. Luscious, erotic nudes that follow them, which are often melancholy and more discomfited. In the 1970’s the imagery took a dramatic turn, strongly influenced by his Greek travels. In response, Brice developed a new vocabulary for these figures: abstracted icons that communicate relationships, theories, and philosophies. He continued to distill these motifs for the rest of his life, reducing, simplifying, “focusing on its essence” as Suzanne Muchnic said in an ARTnews review, 2011.

Drawings from over his long career provide a clear through-line that tracks Brice’s work as a whole: primarily from his early representational drawings to his non-literal, abstracted images populated by iconography relating to classical motifs in Bric’es mature period. The winding road between these two alpha and omega points spaned over 70 years.

WilliamBrice.org’s Gallery dedicated to drawing contain nearly 400 works on paper, spanning from the 1930’s to the artist’s death in 2008. More than any other medium, drawings trace Brice’s developing thinking and ‘hand’ more clearly and fully than any other medium of his oeuvre.

1930’s and 1940’s

1950’s

1960’s

1970’s

1980’s

1990’s.

2000’s