Late in 1969, at the age of forty-eight, Bill Brice painted a small, mostly grisaille picture made up of schematized forms symbolizing the human figure set amidst architectural ruins (figure 1). In its degree of abstraction and its classical motifs, the painting was unlike anything Brice had done during the more than twenty years he had been a practicing artist. This painting proved a fecund anomaly. A few months after its completion, Brice, his wife, and son traveled extensively by boat through the Greek archipelago. Brice was enraptured with the area—its suffused Mediterranean light, its architecture, and the visually stark, interrelated quality of its land and sea. He experienced a rare, galvanizing insight into his work, realizing that he sought something in his own imagery

figure 1. William Brice, Untitled, 1969

oil on canvas, 20 x 16 in.

Collection of the artist

comparable to the grand, idealized universals of classical civilization. The small grey painting he had left behind in his Los Angeles studio had been a physical presentiment of this epiphany. It is a forebear to the large body of work, both drawings and paintings, Brice has since produced.

These singular paintings, made poignant by their fusion of modern and antique, male and female, abstract and realistic, have no counterpart in American art. They are heir to the ambitions of School of Paris painting, filtered through an artist born and trained in New York who spent his entire professional life in southern California. This emphasis on locale has been critical in Brice’s slow evolution as a painter since it is in part the hazy, white light peculiar to Los Angeles that particularly distinguishes his late works. This light informs Brice’s vision as surely as it does that of his good friend and contemporary Richard Diebenkorn. Brice’s profound understanding of Picasso is matched by Diebenkorn’s indebtedness to Matisse. Between them they have posited a figure-landscape ideal that seems uniquely indigenous to Los Angeles. That both these west coast artists chose to circumvent for the most part the achievements of New York school painting is, in itself, remarkable.

Brice’s large body of work, extending from the 1940s to the present, is assembled here for the first time. The connections between the paintings and drawings made before 1970 and the better-known work made after that date are striking. Seen as a whole, the work is the record of a painter working largely outside the artistic fashions of his time, pursuing a style and content that acknowledge the seamless fictions of the past as well as the partial truths of the present. On his canvases, the senses and the intellect are brought together in momentarily civilized harmony.

William Brice was born in Manhattan on April 23, 1921, the second child and first son of Nicky Arnstein and Fanny Brice. His mother was one of America’s greatest comediennes; his father a gambler who had little contact with his children. They lived a privileged existence, but one tempered by Fanny Brice’s great character. Raised by a series of governesses at various households on New York’s Upper East Side, the children were surrounded by the brightest stars of the Broadway stage—Clifford Odets, Bea Lilly, the Gershwin brothers, and Billy Rose, (Fanny Brice’s husband from 1929 to 1938).

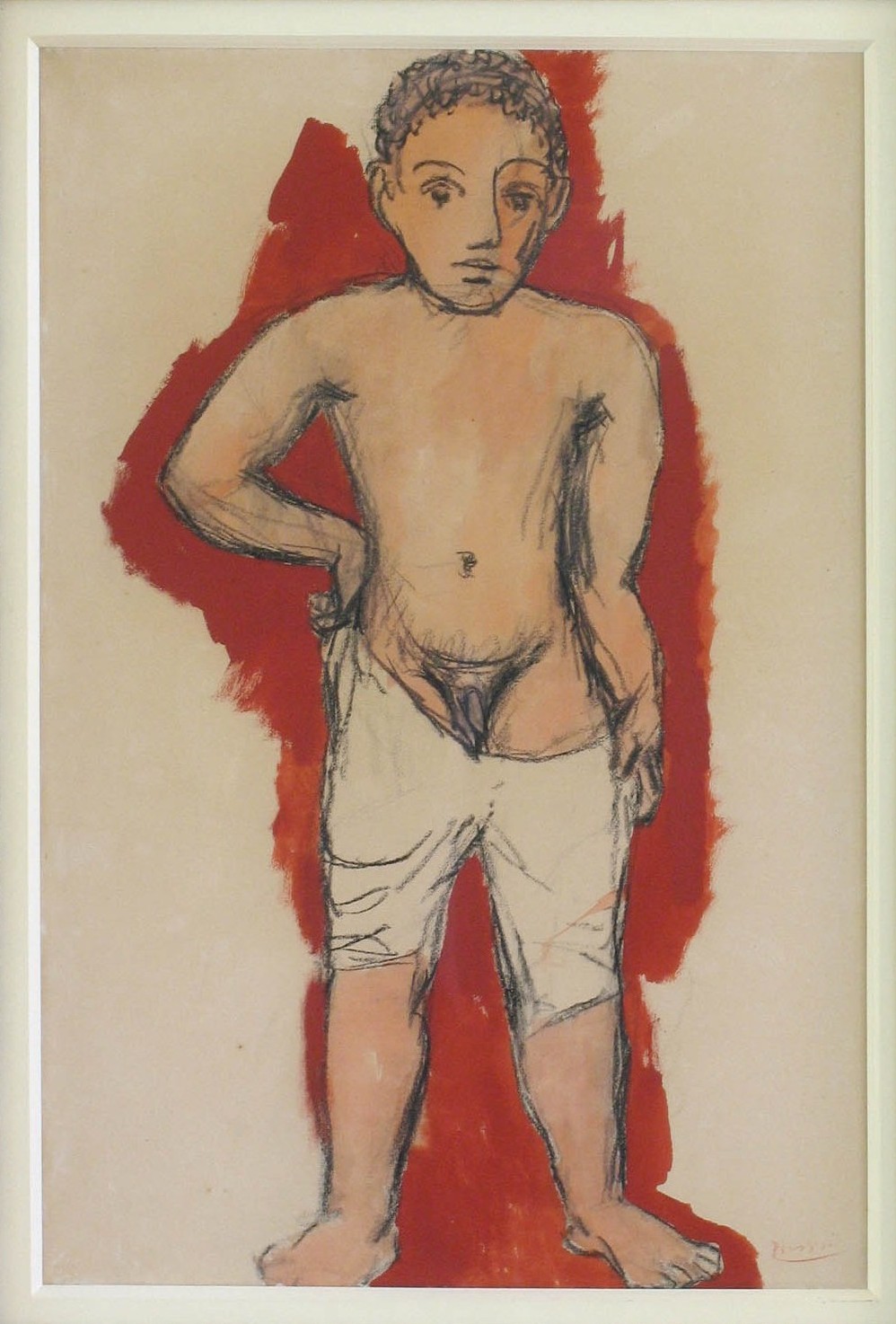

figure 2. Pablo Picasso, A Child in Drawers, 1906

gouache and charcoal on paper, 25 x 16 in.

Collection of William Brice.

It was a disciplined, fast-paced childhood that enforced the value of hard work. Bill studied at Columbia Grammar school. His predilection for the visual arts was apparent; and at the age of thirteen, his art education was taken over by a personal tutor, the painter Henry Botkin. Botkin’s intense dedication to modern art, as he knew it from a long sojourn in Paris during the late 1920s and early 1930s, inspired his young pupil. Today, Brice recalls knowing almost from that moment that he would be an artist. Encouraged by his mother, an amateur painter and accomplished interior decorator herself, he studied both drawing and painting with Botkin. During this period, Fanny Brice took her children to Europe for numerous summer visits, and there young Brice saw the great public art collections of the continent. With Botkin, he also visited the private galleries in New York and met some of the contemporary figures of the New York art scene. By the time the Brice family moved to Beverly Hills in 1937, young Bill had determined he would be a painter. With no aspirations to the theater, he could hope, nonetheless, to become a peer of the genius surrounding him: “I hoped to identify with a world I admired by being a visual artist.”

Indicative of his seriousness, Brice moved back to New York in the late 1930s to live with the Botkin family and attend the Art Students League. Hence, before the age of twenty, he had received a fully classical education in art, supplemented by a firsthand awareness of great paintings through frequent visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the fledgling Museum of Modern Art, and the New York galleries. He saw Picasso’s works of the 1930s at their New York premieres and, at fourteen, he purchased a gouache of a standing young boy done by Picasso in 1906 (figure 2).

When he returned to Los Angeles, Brice finished high school and enrolled at the Chouinard Art Institute. In 1942, he married Shirley Bardeen, a classmate at the coeducational day school Brice had attended. He enlisted in the army that same year, and was discharged for asthma in 1943. Back in Los Angeles, Brice resumed painting and his inquisitive visits to the few local galleries. In the life drawing class he joined at Otis Art Institute, he met Howard Warshaw and, through Warshaw, Rico Lebrun. Brice was familiar with Lebrun’s work, having seen it exhibited at Julian Levy’s gallery in New York in 1945. Lebrun’s charismatic teaching style attracted Warshaw and Brice, and the three became friends. Although their style of painting had little in common, all three believed strongly in the fundamental necessity of drawing. In 1948, Herbert Jepson invited Brice to join Warshaw and Lebrun on the faculty of the Jepson School where drawing’s central role in art-making was emphasized. Relatively quickly, Brice had become a public figure in the burgeoning Los Angeles art community. He had one-person shows at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1947 and at the prestigious Downtown Gallery in New York the following year.

The small paintings of stones

(plate 1) (plate 2) that Brice began to produce in the late 1940s were an early sign of his fundamental attraction to an idealized landscape. Physically compressed, (they vary in size, but average about 6 by 12 inches), the paintings are a renunciation of the socially conscious, figurative work that had occupied Brice over the previous ten years. In direct opposition to the topical melodrama he explored in the mid-1940s, Brice started focusing his vision on the handheld reality of small groups of stones collected on the beach. He recalls being interested at the time in the “slow read” implicit in Piero della Francesca’s paintings and seeking to engender a similar visual effect in his own work. Thus, the backgrounds for the rocks are all simple, orthogonally organized spaces measured and scored to pace the viewer’s scan. Working with a palette knife in somber, natural tones of umber, ocher, green, and violet, Brice sought a solidity and opacity in these images, and the saturation of color innate to rock as his model.

Although small and generated from life, the paintings assume larger, metaphorical meanings—these clusters of stones are best understood as anthropomorphic surrogates. From this point on, simultaneous meanings, multiple allusions, and interchanging significances will animate the best of Brice’s work, substantiating his retrospective opinion that he has never been exclusively either a realistic or a nonobjective painter. As he put it, “I’ve always been interested in the associative, but representation of external reality has not been central.” Besides marking Brice’s initial adoption of symbolic forms, the rock painting are eerily prophetic of the role stone would play as one of the essential elements in his work after 1970. Constant self-scrutiny and a capability for change are evident throughout Brice’s development; the rock paintings attest to his willingness to begin again as an artist, in search of a subject and style more in touch with his vision.

For artists of Brice’s age and maturity, outside both the mainstream of action painting and the heady milieu of New York, the 1950s were often a painful era. Such artists seemed to be missing the long heralded heyday of American art. The vogue of existentialism gave the mass media a standardized ethos to exploit in it reports on American artists, and, for the first time, a sizeable number of Americans began to take notice of the art scene, forming a viable audience for contemporary work. A gregarious man by nature, Brice is a loner as an artist. Though he joined the art faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1953, quickly becoming one of its most popular and respected members, the 1950s remained a period of relative isolation for him as he pursued an out-of-fashion, solitary aesthetic based on direct observation of nature. Nonetheless, his work was shown regularly at respectable, if staid, venues: Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills and the Alan Gallery in New York.