The Painting of William Brice

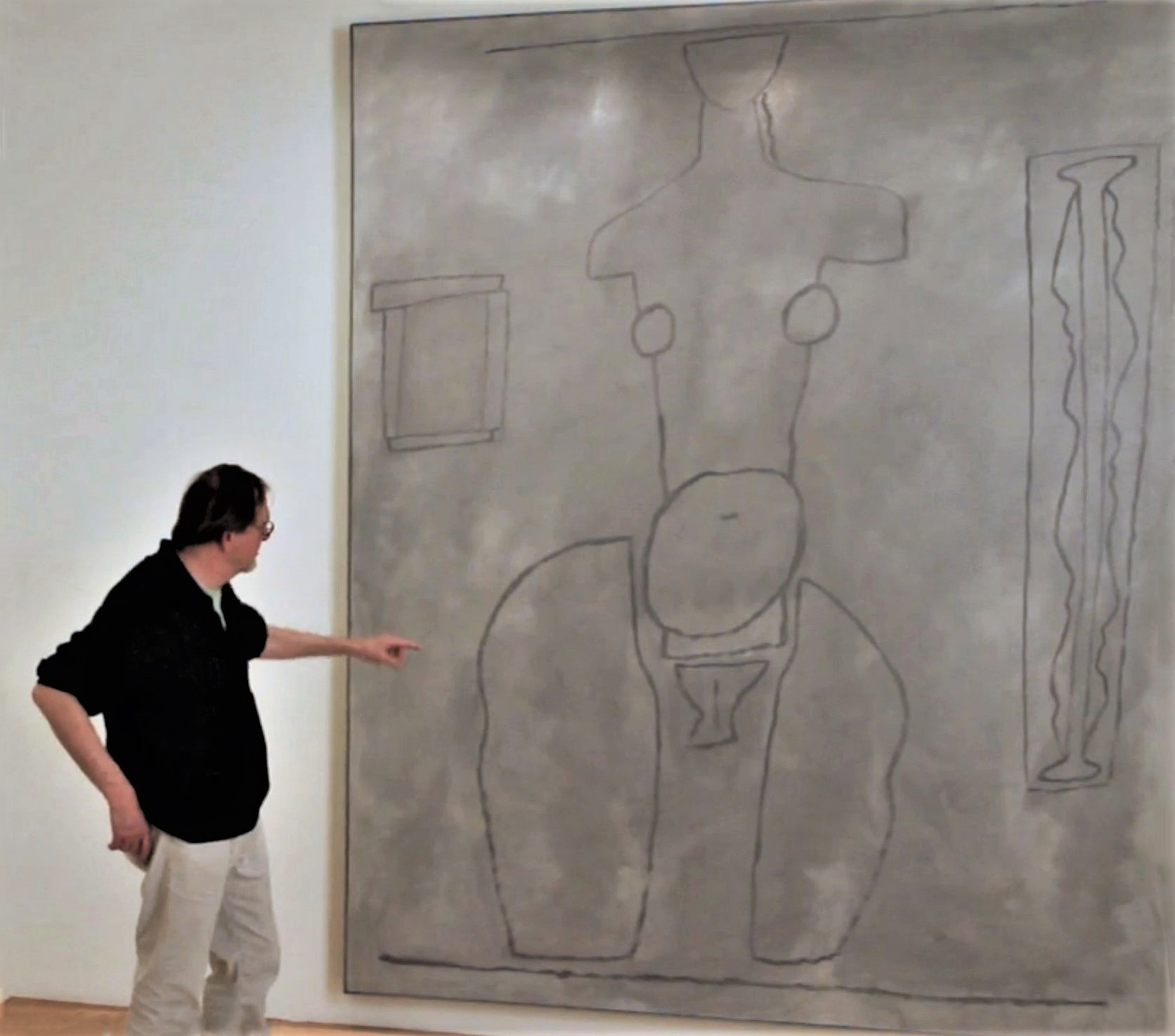

What I want to say about this painting…is that it could easily be misunderstood to the uninitiated. We…see technical mastery in this line. This line in order to make this painting work, it seems quite spontaneous and ‘simple’. I don’t mean simplistic, but simple in that we don’t have too many components; a background grey and then we have the grey lines. The discipline to be able to have a fully and completely engaging painting with such few components says a lot. It speaks of mastery.

Artist Tom Wudl,

Promise and Mastery,

YouTube,

2011

Color and Light

If drawing can perhaps be characterized as an emphasis on structure, line, shape, and form, and painting as an emphasis on color and light, then the ‘lines’ between these characterizations have increasingly blurred due to the contemporary use of technology/new media, collage, and through practice.

Brice occasionally combined both emphases in drawings and alternately in paintings as the above photograph of his “line” “shape” painting of a Venus figure seen with artist Tom Wudl shows.

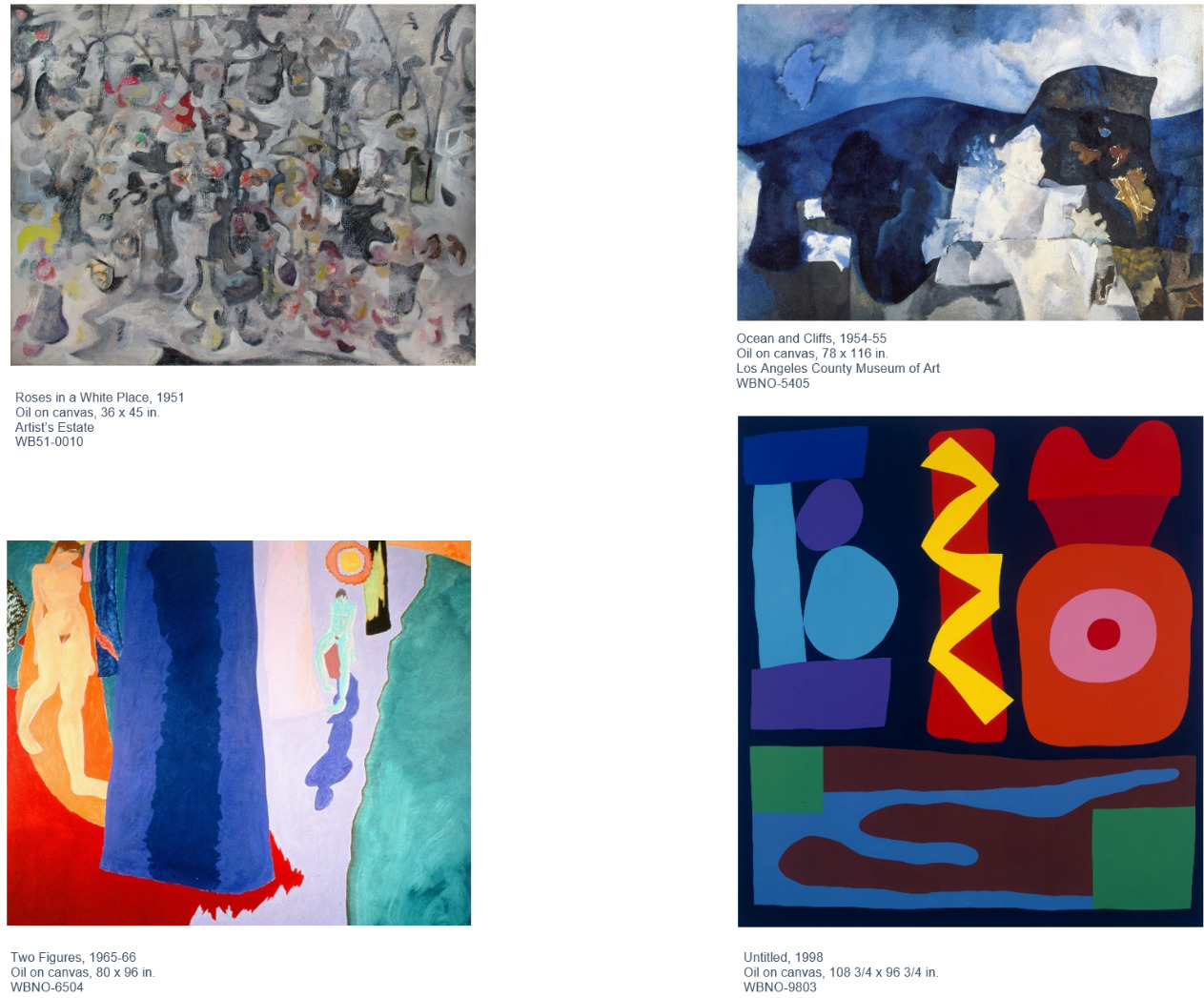

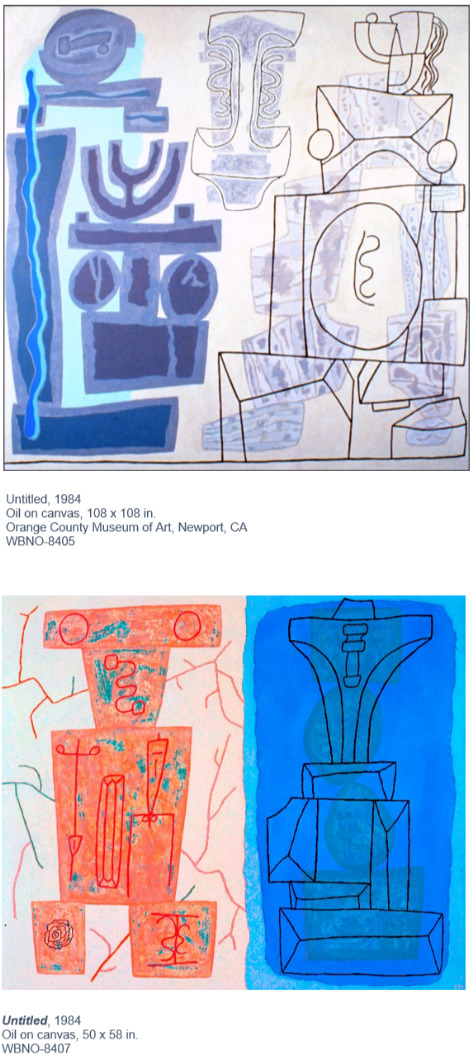

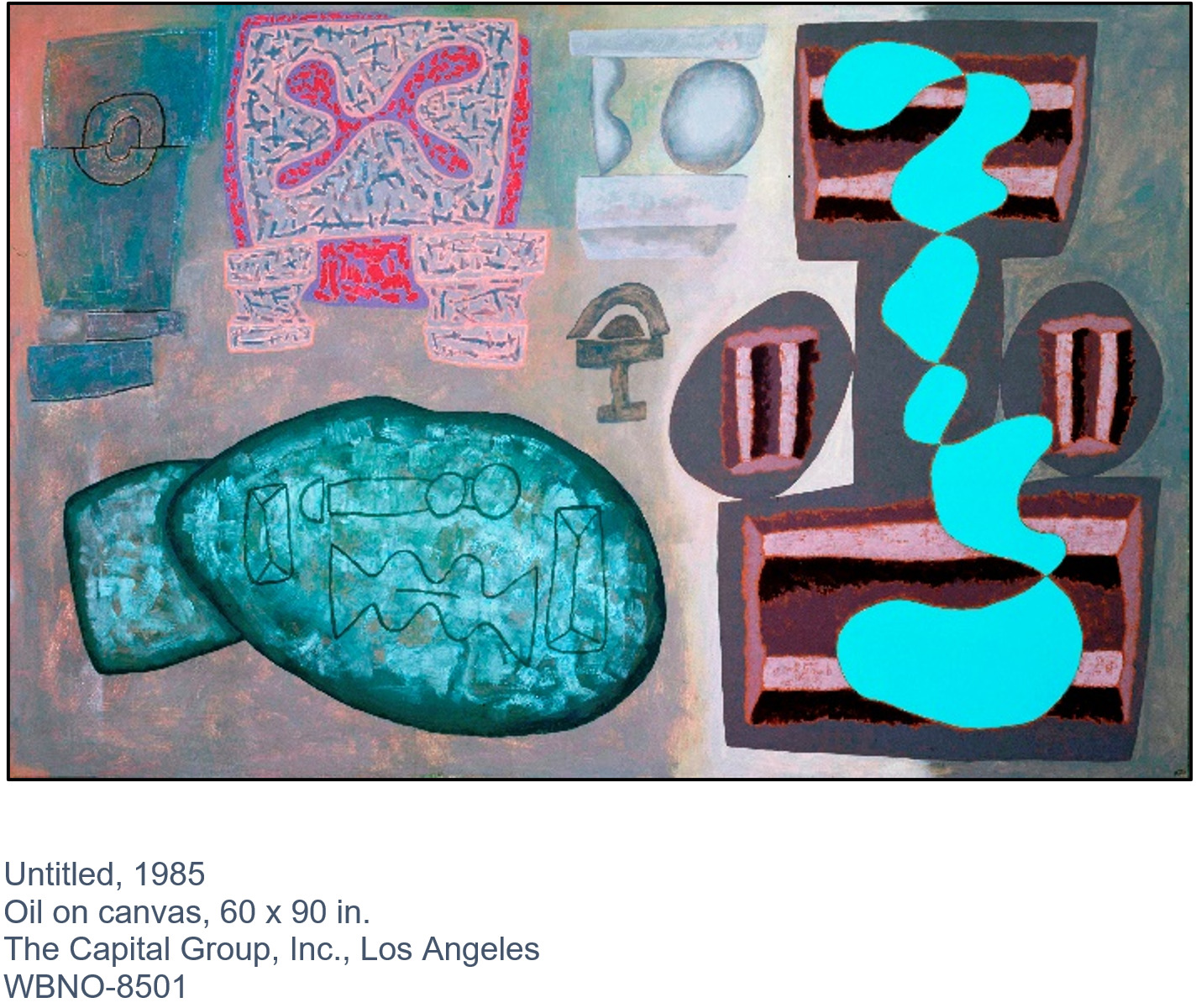

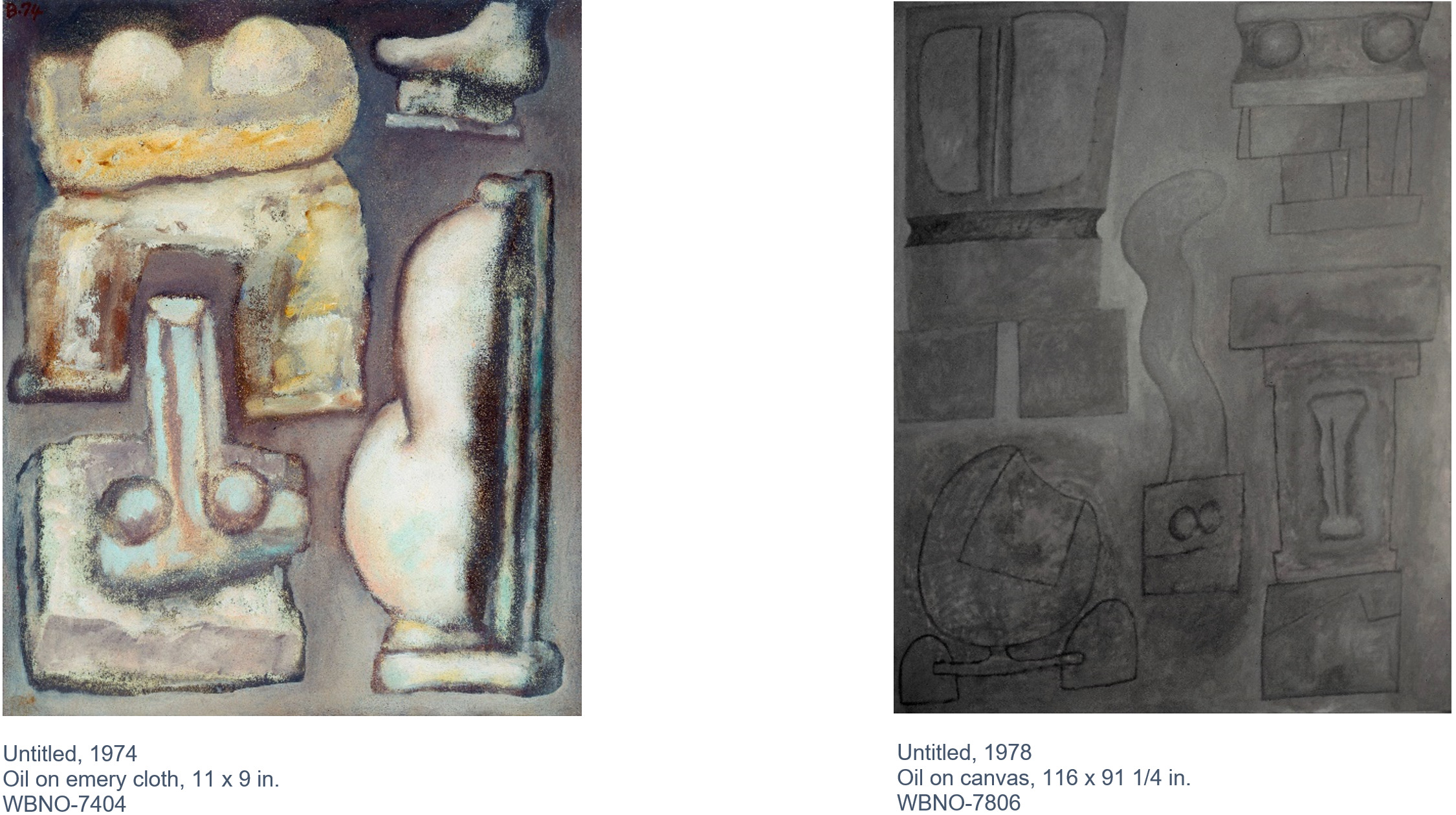

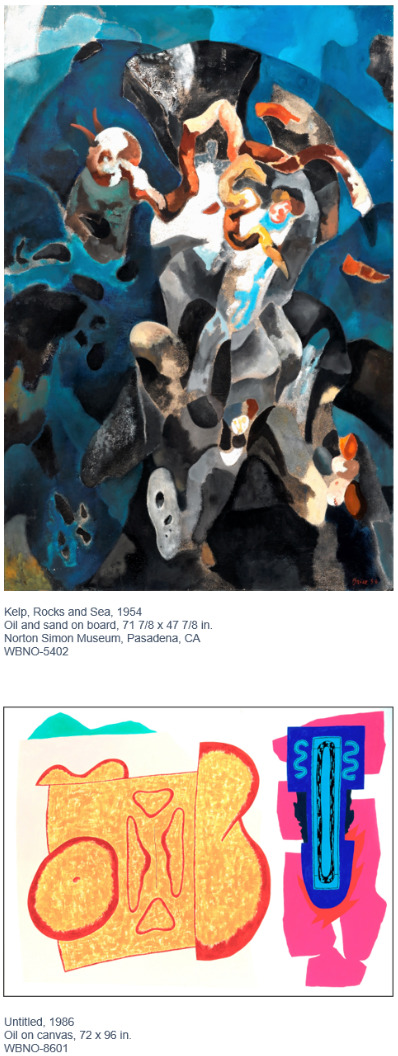

However, Brice’s four paintings directly above firstly rely on his approaches to color and light.

Palette

Brice’s palette ranged from low chroma greys as seen in his Untitled, 1978 big, grey Venus figure (with Tom Wudl) at the top of this blog and the muted browns/stone/earth tones of his 1954 Mottled Things, (above), to his luminous and bright colored 1978 Untitled painting (above, left) with its sea and sky blues and rusted pinks, to his zingy, high-key color 1998 Untitled painting (above, right).

Weight and Balance

Bill, everywhere in his work was playing the most beautiful and interesting games of weight and division and structure, and then on top of that layering these luscious, elegant, delicate colors. So, there is a kind of lyricism laying on top of a fierce and almost primitive strength. This gives the work power and delicacy that is so beautiful.

David Rodes,

Curator Emeritus, Grunwald Center for Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum,

Between Lyricism and a Dark, Sexual Energy, YouTube

So, I began to think of a juxtaposition that would tend to break or separate or take apart this composite. And so, for me the one thing that I felt I knew…was some aspect of an equilibrium, which had very little transition between it, that is like sewing one part to the other part. That would exist in a state of tension that had to do with the tension between the optical, the physical qualities, the associative qualities, that they’re separated from the psychological.

But it was really a balance of these different differentiation…that a lot of things became issues of that.

And it was also the idea that [my “subject references”] were increasingly iconic. By iconic I mean (inaudible)… and singular. So, the iconic, the Russian icon, the Czechoslovakian icon, ah—the idea of the one, one, one. There’s a tendency to draw you in and to absorb its powers. Its hypnotic power. It offers you no entertainment, no diversities. It’s one. It’s absolute. It’s singular. And I had the feeling that what you have with that is you’re drawn into the work and you’re held in the work, and perhaps you’re even mesmerized, entranced. And it’s contemplative in that respect. You’re lost in it.

Now, when you have that and you have more than one icon, then you have a problem. You have an issue of what’s the interval between icons that permit you to go in, get out, get into the next one without them canceling their powers. And that’s been an issue for me in my work because I’m increasingly working in composites. I also felt, and have examined, is this frontality necessary to me. As you can see in the earlier room, the room with the “Fractured Land,” there’re some paintings, there’s a lot of interlocking of forms, a lot of intervals of space overlapping. And I, from the little ones on, was getting to kind of an alphabet like A, B, C, D. I said, “Gee, does it have to be this simple?” But I began to feel more and more that was an absolute necessity of an expressive nature for me. That although the other aspect may be very entertaining, it did not have the force of expression that I needed.

I began to work with the idea of overlaying composites. So, I could have two and three layers of space all frontal. So, I could have something become two and three things at one time.

William Brice,

MOCA Mid-Career Retrospective Walkthrough,

YouTube

1986

Scale vs. Size

Brice’s paintings range in scale in actuality and by impression. Small-sized paintings like the 1974 painting above on the left may appear monumental while very large paintings such as the 1978 painting above on the right may feel intimate and muted. Or huge paintings may be bold and electric.

Local: Southern Californian and Greek Light

Brice remained deeply attracted to Southern California’s light, the quality of which he also found in abundance and distilled in Greece.

[Brice was an] artist born and trained in New York who spent his entire professional life in Southern California. This emphasis on locale has been critical in Brice’s slow evolution as a painter since it is in part the hazy, white light peculiar to Los Angeles that particularly distinguishes his late works. This light informs Brice’s vision as surely as it does that of his good friend and contemporary Richard Diebenkorn…

[T]he brilliant Aegean sunlight reinforced Brice’s Mulholland era discovery that “things were malleable”. In Greece, light rendered stone visually liquid and gave water a palpable tactility. Brice experienced distinct states of sensation of the light’s effects, and he stored them in memory in hopes of provoking comparable sensations in his paintings…

Richard Armstrong,

Director, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation,

William Brice’s Essential Elements,

MOCA Exhibition Catalogue Essay,

1986

* * *

[Brice] actually revised the tack of reductivist art to remind us that painting can still be something more than pure phenomenon or mere formality. The net effect of his astringent cocktail of sensibilities makes a place where the lyric meets the epic, energy confronts exhaustion, and rapture boogies with anxiety.

William Wilson,

Brice’s Paintings Zing,

Chief Art Critic, Los Angeles Times,

November 16, 1998